Source: Laborers, Servants, and “Chosen Women” in the Inca Empire

Selected by John Verano. From Craig Morris and Adriana von Hagen, The Incas (London: Thames & Hudson, 2012).

Morris and von Hagen, The Incas, p. 60

The men and women who worked for the state fell into several categories based on whether they worked full-time or seasonally, and whether their service removed them permanently from their native communities. Probably the most common labor category was called mit’a, comprising able-bodied heads of household who worked seasonally. They retained ties to their local communities even though many traveled substantial distances from their homes. The Incas also used this system of rotating service to recruit soldiers.

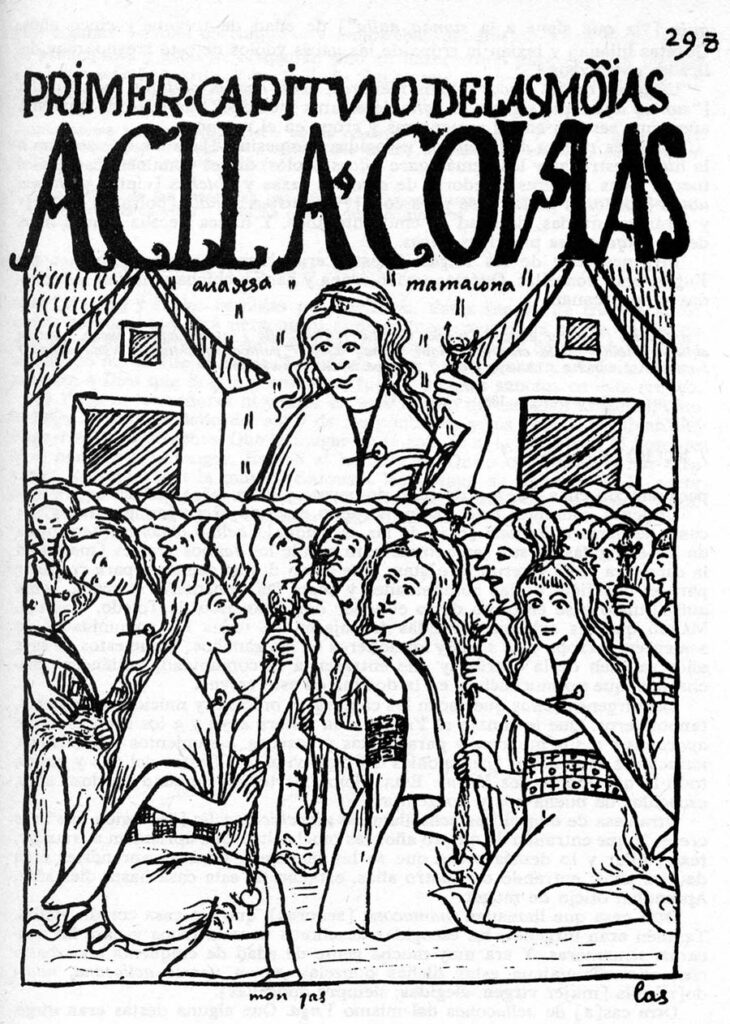

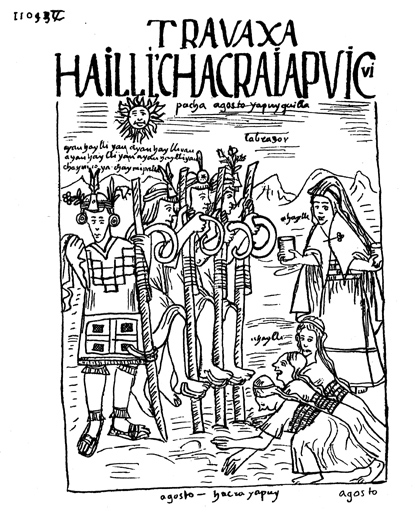

In contrast to the rotating workers, female aclla—weavers, brewers, and religious officials—and male yana (personal retainers) performed full-time service and usually lost the ties to their communities. Yana have often been equated with slaves, but this is a serious simplification, and their loss of community ties should not be compared with enslavement in the European sense. The state supplied them with food and other needs, and many yana and aclla occupied privileged positions; indeed, the Incas elevated some yana to kuraka [lord] status.

Mitmaq formed the most unusual category: entire communities relocated to new areas that required their services. The Incas transferred experienced farmers, for instance, to newly terraced valleys to increase production… They also provided strategic services to the state, in addition to their economic functions. The Incas moved loyal groups to areas of rebellious peoples, and dispersed less compliant communities among more reliable ones.

Selected by John Verano. From Terence D’Altroy, Provincial Power in the Inka Empire (Washington: Smithsonian Institution Press, 1992).

D’Altroy, Provincial Power in the Inka Empire, p. 154

In numerous areas, the Inkas appropriated and intensified lands around major state installations to support the personnel stationed at those locations. The state also increasingly developed agricultural zones set aside for specialized production, the most remarkable known example being the state farms of Cochabamba, Bolivia. There the emperor Wayna Qhapaq ordered virtually all native residents removed from the valley and brought in 14,000 agricultural workers to farm the lands, both as permanent colonists and as corvée laborers. The maize harvest was temporarily housed in 2,500 storehouses at Cotapachi before its transport to Cuzco, where it was reportedly used to feed the Inka armies.

Discussion Questions

- How would you define slave status? In what ways does that definition fit laborers for the Incan state? In what ways does their status differ?

- Compare the two images of Incans working for the state. What kinds of labor are being performed? How are the laborers being supervised or controlled? To what extent are the laborers portrayed as distinct individuals? What other similarities or differences do you notice?

Related Primary Sources

- Cobo, Bernabé. History of the Inca Empire: An Account of the Indians’ Customs and Their Origin, Together with a Treatise on Inca Legends, History, and Social Institutions. Translated by Roladn Hamilton. Austin: University of Texas Press, 1979.

- Guaman Poma de Ayala, Felipe. El primer nueva corónica y buen gobierno. Edited by Rolena Adorno, John Murra, and Jorge Urioste. Mexico: Siglo Veintiuno, 1980.

- The Law of Enslaving Starving Children

- Murúa, Martín de. Historia general del Piru: Facsimile of J. Paul Getty Museum Ms. Ludwig XIII 16. Edited by Barbara Anderson and Thomas Cumming. Los Angeles: The Getty Research Institute, 2008.

Related Secondary Sources

- Gose, Peter. “The State as a Chosen Woman: Brideservice and the Feeding of Tributaries in the Inka Empire,” American Anthropologist 102, no. 1 (2000): 84-97.

- Murra, John V. The Economic Organization of the Inka State. Research in Economic Anthropology. Supplement, 1. Greenwich, CT: JAI Press, 1980.

- Rowe, John H. “Inca Culture at the Time of the Spanish Conquest.” In Handbook of South American Indians, ed. Julian H. Steward, 2:183–330. Washington, D.C.: Bureau of American Ethnology, 1946.

- Urton, Gary, and Adriana von Hagen, eds. (2015) Encyclopedia of the Incas. Lanham, MD: Rowman & Littlefield Publishers, 2015. See especially Irene Silverblatt, “Acllacuna” and Terence D’Altroy, “Labor Service.”