Source: Aztec Slaves

Selected by John Verano. From Michael Smith, The Aztecs, 3rd edition. Malden, MA: Wiley-Blackwell, 2012.

Smith, The Aztecs, p. 141-142

At the bottom of the social scale were the slaves, tlacotin (sing. tlacotli). People became slaves through debt or punishment, but not through birth; slavery was not hereditary. Slaves could marry, have children (who were free) and even own property. Anyone could own a slave, but most slave-owners were nobles. The owner was responsible for feeding and housing the slave and had control over the slave’s labor.

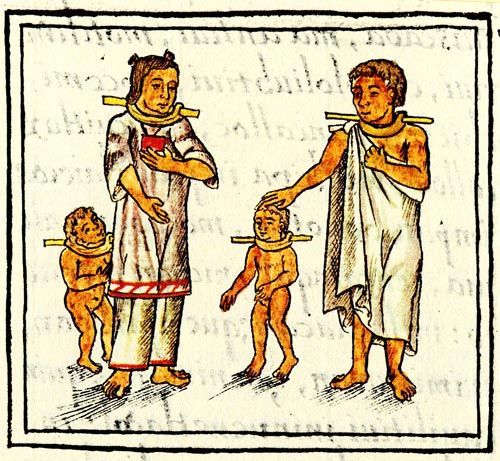

People sold themselves into slavery when they could not support themselves. During the great famine of the 1450s, for example, many Aztecs sold themselves to people of the Gulf Coast where economic conditions were better. Failure to pay taxes was another way to become a slave, with the purchase price going to cover the debt. Some other crimes were also punishable in this way. The change in status from free citizen to slave was an official act that had to be witnessed formally by four officials. Some pochteca merchants specialized in trading slaves, and several markets were known as centers for the slave trade. Slaves for sale were identified by large wooden collars [to make escape more difficult from the market].

Translated from the Spanish. Diego Durán, Book of the Gods and Rites and The Ancient Calendar, translated by Fernando Horcasitas and Doris Heyden (Norman: University of Oklahoma Press, 1971), 279-280, 282, and 286. Contributed by John Verano.

Book XX: Which treats of the Tianguiz, which means Market place, and of the slaves who were brought there to impersonate gods and to be sacrificed

The masters took the slaves to the [market]: some took men, others women, others boys or girls, so that there would be variety from which to choose. So that they would be identified as slaves, they wore on their necks wooden or metal collars with small rings through which passed rods about one yard long…

In times of famine a man and wife could agree to a way of satisfying their needs and rise from their wretched state. They could sell one another, and thus husband sold wife and wife sold husband, or they sold one of their children if they had more than four or five. These could be redeemed later by returning their price to those who had bought them…

Regarding the second [type of slaves], men captured in war…It was certain and sure that such captives were to serve as victims in sacrifice…because they had been brought exclusively to be sacrificed to the gods…

Translated from the Spanish. Bernardino de Sahagún, General History of the Things of New Spain by Fray Bernardino De Sahagún: The Florentine Codex, translated by Charles Dibble and Arthur Anderson (Santa Fe: School of American Research, 1953), 23. Contributed by John Verano.

The Eighth Chapter: Famine and Slavery

The Eighth Chapter telleth how they held in dread hunger and famine when One Rabbit ruled the year count… This was a time when they bought people; they purchased men for themselves. The merchants were those who had plenty, who prospered…In the homes of [such men] they crowded, going into bondage…the orphan, the poor, the indigent, the needy, the pauper, the beggar, who were starved and famished[.] At this time one sold oneself. One ate oneself; one swallowed oneself. Or else one sold and delivered into bondage his beloved son, his dear child.

Discussion Questions

- How do we know that the people depicted in the image are slaves?

- Why did some Aztecs sell themselves or their families into slavery during periods of famine? What do you think Bernardino de Sahagún meant when he described this choice as eating or swallowing oneself?

Related Primary Sources

- Acts of Child Sale in the Black Sea

- Concerning Persons and Divisions of Persons

- The Law of Enslaving Starving Children

- Mibiki and Slavery in Medieval Japan

- Visigothic Manumission Charters

Related Secondary Sources

- Clendinnen, Inga. “The Cost of Courage in Aztec Society.” Past and Present 107 (1985): 44-89.

- Millerhauser, John. “Debt as a Double-Edged Risk: A Historical Case from Nahua (Aztec) Mexico.” Economic Anthropology 4 (2017): 263-275.

- Offner, Jerome. “The Future of Aztec Law.” In Legal Encounters on the Medieval Globe, edited by Elizabeth Lambourn, 1-32. Kalamazoo: Arc Humanities Press, 2017.

- Rio, Alice. “Self-Sale and Voluntary Entry into Unfreedom, 300-1100.” Journal of Social History, 45, no. 3 (2012): 661-685.

Themes

Captives, Children, Images, Ransom, Self-Sale, Trade, Violence