DBQ: Slavery and Labor

Document-Based Question: Explain the different kinds of labor and service that enslaved people performed during the period before 1500.

In your response you should do the following:

- Respond to the prompt with a historically defensible thesis or claim that establishes a line of reasoning.

- Describe a broader historical context relevant to the prompt.

- Support an argument in response to the prompt using at least six documents.

- Use at least one additional piece of specific historical evidence (beyond that found in the documents) relevant to an argument about the prompt.

- For at least three documents, explain how or why the document’s point of view, purpose, historical situation, and/or audience is relevant to an argument.

- Use evidence to corroborate, qualify, or modify an argument that addresses the prompt.

Contributed by Hannah Barker. This contribution CC BY-NC-ND 4.0.

Document 1

Source: An anecdote from the Book of Songs, a massive collection of songs with extensive musical, literary, and cultural commentary. It was written by Abu al-Faraj al-Isbahani, a tenth-century scholar and government administrator who lived in Baghdad under the Abbasids.

Shāriya belonged to a Hashimite[1] woman from Basra, a descendant of Jaʿfar ibn Sulaymān. The woman took her to Baghdad intending to sell her. She first presented her to Isḥāq ibn Ibrāhīm al-Mawṣilī who offered three hundred dinars[2] but then, thinking the amount excessive, withdrew the bid. She then approached Ibrāhīm ibn al-Mahdī and presented Shāriya to him. He haggled over her price. Shāriya’s owner replied: ‘I have an offer out to Isḥāq ibn Ibrāhīm of three hundred dinars but you, my lord – may God keep you – are far more deserving of her.’ He ordered that very amount to be measured out and given to her. He then summoned the head of his household: ‘Secret this young (slave) woman away for a year and tell the other women singers to teach her all they know.’ A year later she was brought before him; he examined her thoroughly and listened to her sing. He then contacted Isḥāq ibn Ibrāhīm al-Mawṣilī, inviting him to see Shāriya and hear her perform. ‘I mean to sell her,’ he said, ‘Would you consider buying her?’ Isḥāq: ‘I’ll take her for three thousand dinars, which I think a fair price.’ Ibrāhīm: ‘Do you not recognize her?’ ‘No.’ ‘She is the young slave that the Hashimite woman offered to you for three hundred dinars, but you turned her down.’ Isḥāq, much embarrassed, expressed his astonishment at how she had turned out.

[1] Descended from the Prophet Muḥammad.

[2] Gold coins minted by the Abbasid caliphate.

Document 2

Source: A legal document drawn up in the city of Barcelona in 1399. Pere Vyturbi, a merchant, promised to free Caterina, his slave, on the condition that she continue to serve his family for eight years and breastfeed his youngest son.

The Honorable Pere Vytubri, merchant and citizen of Barcelona, noting that Caterina, his slave, servant, and captive, of the race of the Tartars, will have breastfed some of his sons and daughters and that now she has been breastfeeding a certain other son of his called Joan, and noting that she had always been faithful and legal[1] to him; on that account wanting to make a certain freely given agreement and promise to you [Caterina], and to the notary[2] [whose name, Arnau Piquer, is] written below, likewise stipulating that if you serve me and mine and whomsoever I wish well and according to the law from now for eight years continuously and not less, and while you breastfeed the said my son Joan you will live chastely and will not have done anything by which your milk was caused to deteriorate or harmed my same son in any way, I will make you free and manumitted and from now on through this promise I make and call you free and manumitted but you must breastfeed the said my son.

[1] She always acted according to the law.

[2] The legal professional who composed this document in the proper form.

Document 3

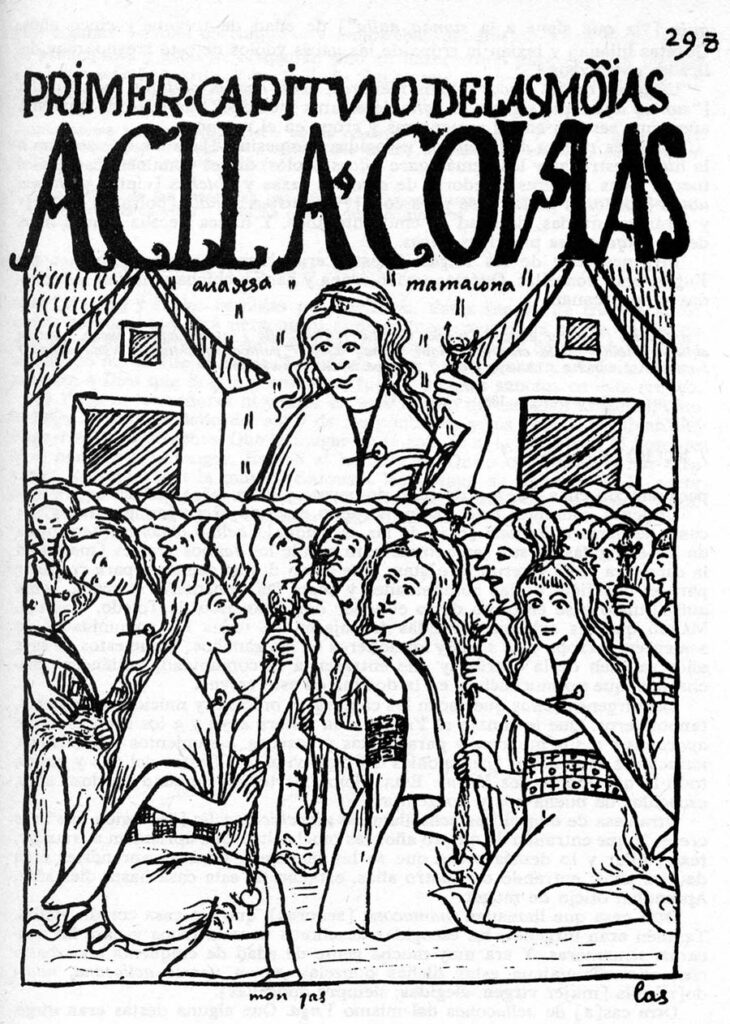

Source: A group of Incan “chosen women” (sg. aclla, pl. acllacuna) spinning thread. Illustration from a chronicle of Andean history by Felipe Guáman Poma de Ayala, a Quechua nobleman. After finishing the chronicle in 1615, he sent a copy to King Philip III of Spain.

Document 4

Source: Description of Taghāzā, a town in the Sahara desert along the caravan route between Morocco and Mali in West Africa. From the Travels of Ibn Baṭṭūṭa, a fourteenth-century Islamic scholar from Morocco who traveled widely, reaching as far as India and China. His visit to Mali between 1351 and 1354 was his last major journey.

After 25 days we arrived at Taghāzā. This is a village with nothing good about it. One of its marvels is that its houses and mosque are of rock salt and its roofs of camel skins. It has no trees, but is nothing but sand with a salt mine. They dig in the earth for salt, which is found in great slabs lying one upon the other as though they have been shaped and placed underground. A camel carries two slabs of it. Nobody lives there except the slaves of the Masūfa who dig for the salt. They live on the dates imported to them from Darʿa and Sijilmāsa, on camel-meat, and on anilī imported from the land of the Sūdān.[1] The Sūdān come to them from their land and carry the salt away… The Sūdān use salt for currency as gold and silver is used. They cut it into pieces and use it for their transactions. Despite the meanness of the village of Taghāzā they deal with qinṭār upon qinṭār of gold there. We stayed for ten days, under strain because the water there is brackish. It is the most fly-ridden of places.

[1] Literally translated, Sūdān means Blacks. It was used in medieval Arabic as a generic term for dark-skinned Africans.

Document 5

Source: Muʿtamad Khan, a Persian scholar who joined the court of the Mughal ruler Jahangir and chronicled his reign. In his chronicle, Muʿtamad Khan recorded the death in 1627 of one of Jahangir’s main enemies and rivals for control of the Deccan region of India: Malik Ambar, a former military slave and feared Regent of the Sultanate of Ahmednagar.

Intelligence now arrived of the death of ʿAmbar the Abyssinian, in the eightieth year of his age, on 31st Urdibihisht.[1] This ʿAmbar was a slave,[2] but an able man. In warfare, in command, in sound judgement, and in administration, he had no rival or equal. He well understood that predatory warfare, which in the language of the Dakhin[3] is called bari-giri. He kept down the turbulent spirits of that country, and maintained his exalted position to the end of his life, and closed his career in honour. History records no other instance of an Abyssinian slave arriving at such eminence.

[1] The second month of the Persian solar calendar, corresponding to late April and early May.

[2] Malik ʿAmbar had been manumitted many years ago, but Muʿtamad Khan still makes reference to his status.

[3] The Deccan region of India.

Document 6

Source: Chapter from a treatise on earning divine favor by doing your job well. Written by al-Subkī, an expert in Islamic law who lived in the Mamluk sultanate of Egypt and Syria during the fourteenth century. Although he is supposed to offer advice for young enslaved men working as cupbearers, in this passage al-Subkī instead criticizes the motives of the Mamluk elite who own cupbearers.

The Twenty-Seventh Example: The Cupbearers. Their responsibility is to bring drinks. They are among the ugliest innovations[1] and the most vainglorious in the world. For the Companions, may God be pleased with them, (and their sovereignty was greater than that of the kings of the Turks[2] and the possessions that were in their hands exceeded these possessions to an extent that only God can count) drank water from their cupped hands. For all of the people who hold these offices [of cupbearer] there is appropriate advice on how to do their jobs.

[1] Innovations, or departures from the tradition of the Prophet Muḥammad and his companions, was a popular topic for moralizing treatises.

[2] Mamluk rulers were usually referred to as Turks because of their origins in the steppe north of the Black Sea.

Document 7

Source: A decision of the Ducal Court, the highest court of appeal in the judicial system of Venetian colony of Crete, issued on December 17, 1381. In this decision, the court rules that the son of a free man and an enslaved woman (who was later freed) should be raised by his father as his adopted son and heir.

By the excellent lord Peter Mocenigo, honorable Duke of Crete, and his counsel, it is said in agreement that John, the young child, son of Maria, who was the former slave of Lanzaroto Demolino, should be handed over to the said Lanzoroto who was content to give him assets and care for him as an adopted son. It is in this condition that the said John from now forward is liberated and free and is his own man, and not subjected to any bonds of servitude, but should be bequeathed and inherited as liberated and free.