Source: Initial Q from the Vidal Mayor: Two Soldiers Leading Two Slaves before a King

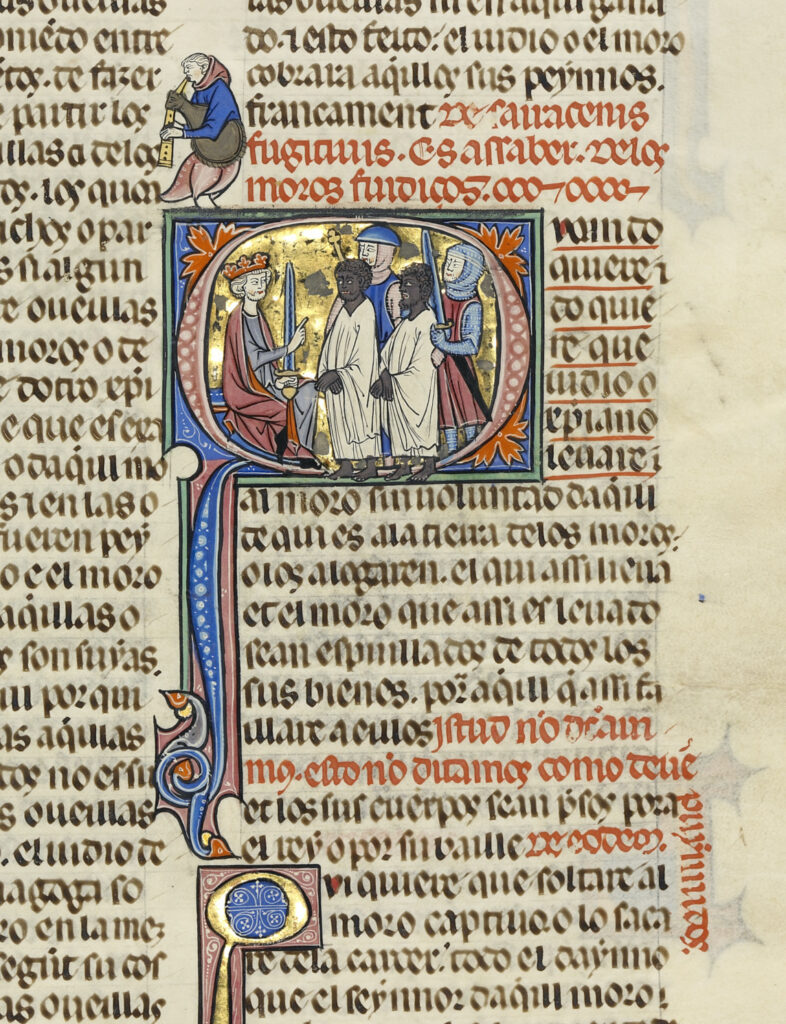

What did medieval slavery look like? The answer varies, and so does the evidence that medieval images offer about this. One good example is this historiated initial[1] from a Navarro-Aragonese law manuscript known as the Vidal Mayor, produced around 1300, probably for King James II of Aragon (r. 1291-1327). The work is a vernacular translation of a mid-thirteenth-century Latin law code intended to regulate nearly all aspects of medieval Aragonese society. The initial shown here introduces a law, or fuero, which concerns the ownership of slaves, including such matters as their owners’ right to pursue them if fugitive and be compensated if deprived of them, as well as of the slaves’ status in relation to the king. The Iberian Peninsula at this time was divided into several Christian-ruled kingdoms based in the north and a Muslim-ruled sultanate in Granada to the south: all were ethnically and culturally diverse, and all depended on enslaved people for many kinds of work. In the Crown of Aragon, where this manuscript was made, most such slaves were Iberian Muslims captured in the course of the Crown’s expansion into neighboring Muslim-ruled lands over the course of the thirteenth century.

The text of the fuero reflects this in its use of the word moro,[2] which at this date could mean both a Muslim person and a slave, a usage paralleled in the manuscript’s bilingual rubric[3] by the Latin word sarracenus (Saracen). But the initial’s visual language is quite different: it depicts two dark-skinned captives presented to a pale-skinned king by two equally white soldiers. An unprepared modern viewer might take the slaves’ color, curly hair, and distinctive facial features, which echo a sometimes pejorative stereotype used for people of African origin in European art, as evidence that slaves in thirteenth-century Aragon were predominantly black. In fact, this was not the case: relatively few black Africans were enslaved in Aragon at this time. Instead, these figures draw on a visual shorthand that was often used to represent slaves both in medieval Iberia and elsewhere, including some Islamicate lands (see https://medievalslavery.org/13th-century/). Although images like this one have a great deal to tell us about the prejudices associated with dark skin and Africans in late medieval Europe, they prove unreliable as literal historical documents. They also offer an important caution against assuming that slavery was limited historically to certain races and ethnic groups.

[1] The first (initial) letter of a manuscript line, containing an identifiable scene or figures, which may or may not relate to the text (see https://www.bl.uk/catalogues/illuminatedmanuscripts/GlossH.asp).

[2] This word is sometimes translated as “Moor,” but the meaning of this early modern English term differs substantially from the medieval usage discussed here, so it is left in the original.

[3] A title or instruction, often written in red, that helps to identify the components of a text. (See https://www.bl.uk/catalogues/illuminatedmanuscripts/GlossR.asp).

Contributed by Pamela Patton. This contribution CC BY-NC-ND 4.0.

Discussion Questions

- How do costume, scale, and other attributes work with stereotype to signal these figures’ status in relation to the king?

- Assuming that this manuscript was made for a royal or other elite viewer, how might initials like this one have altered or enhanced their reading of the text?

- Can you think of other works of art, premodern or modern, that use stereotypes in a similar way to this work?

Related Primary Sources

- María de los Desamparados Cabanes Pecour, Asunción Blasco Martínez, and Pilar Pueyo Colomino, Vidal Mayor: Edición, introducción, y notas al manuscrito (Zaragoza: Libros Certeza, 1996). This is a critical edition of the text.

- Christian Capture of Muslim Captives and Slaves in the Thirteenth-Century Crown or Realms of Aragon

- Concerning Sellers of Male and Female Slaves

- Indian soldiers from the province of Coritiba, bringing back captives

- Khubilai Khan Hunting

- The Miracle of the Relic of the True Cross on the Rialto Bridge: Enslaved Africans in Renaissance Venice

- Misdeeds of Catalan Corsairs

Related Secondary Sources

- Constable, Olivia Remie. “Muslim Spain and Mediterranean Slavery: The Medieval Slave Trade as an Aspect of Muslim-Christian Relations.” In Christendom and Its Discontents. Exclusion, Persecution, and Rebellion, 1000–1500, ed. by Scott L. Waugh and Peter D. Diehl, 264-284. New York: Cambridge University Press, 1996.

- Patton, Pamela A. “Color, Culture, and the Making of Difference in the Vidal Mayor.” In Toward a Global Middle Ages: Encountering the World Through Illuminated Manuscripts, ed. by Bryan C. Keene, 182-189. Los Angeles: J. Paul Getty Museum, 2019.

- Phillips, William D. Slavery in Medieval and Early Modern Iberia. Philadelphia: University of Pennsylvania Press, 2014.