Source: Zuwīla, Libya

Contributed by Paul J. Lane. This contribution CC BY-NC-ND 4.0. This image published in D.J. Mattingly, M.J. Sterry, and D.N. Edwards, “The Origins and Development of Zuwīla, Libyan Sahara: An Archaeological and Historical Overview of an Ancient Oasis Town and Caravan Centre” Azania: Archaeological Research in Africa 50, no. 1 (2015): 27-75.

Zuwīla was locate at the strategic intersection of important north-south Trans-Saharan trade route and another running northeast. A new Ibadite kingdom emerged here in 918, under the authority of Abd Allāh ibn al-Khaṭṭāb al-Hawwārī. Although al-Bakrī writing in the late eleventh century described Zuwīla as a town ‘with no walls’, archaeological research has shown that in the tenth to twelfth centuries, the settlement was more complex. The different elements included a sizeable, undefended oasis town with mud-brick housing that was probably first settled in the first to sixth centuries CE. This area also included the town’s first congregational mosque and a qaṣr, or castle, of possibly late Garamantian origin. To the north of this are the substantial remains mud-built fortifications enclosing around 4.5 hectares (around 11.12 acres), encompassing the surviving sections of the late medieval and early modern town. In addition to the fortifications and the remains of the unenclosed settlement, a number of tombs built from white mud-bricks coated with stone slabs have also been found (although they were largely destroyed by Islamic fundamentalists in 2013). When first documented by archaeologists, the upper sections still retain a covering of plaster painted with Kufic inscriptions. These tombs, like the rammed earth (pisé) fortifications, have been recently radiocarbon dated to the tenth or very early eleventh century CE, corresponding to the early period of the Banu Khaṭṭāb kingdom.

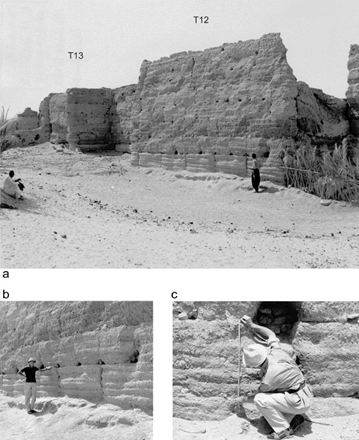

In plan, this fortified settlement was roughly trapezoidal. T surrounding walls were about a metre (about 3 feet 3 inches) thick at their base originally and mostly between 6.3–6.5 metres (c. 20’ 8” – 21’ 3” ft) high but in places reached 7.2 metres (c. 23’ 7”4). Along the walls, at roughly 10-15 metre (c. 32’ 9” – 49’ 2”) intervals, are a series of rectangular bastion towers that project around 3-4 metres (c. 9’ 10” – 13’ 1”) beyond the curtain wall. Traces of thirty-six of these have been recorded, but there were perhaps as many as thirty-eight, originally.

An interesting feature of the fortifications is that instead of being built of mud-brick, the more standard building technology for this area, the technique known as pisé, or rammed earth was used. It is possible that knowledge of this building technique came from southern Morocco where it is known to have been far more widespread, and was perhaps introduced by masons especially recruited to oversee the task, although there are no textual sources confirming this. Importantly, this building method involves mixing gravelly sand and mud with water, and tamping this into a layer using a series of wooden frames or coffers. Straw, lime, cow dung, and/or gravel (as at Zuwīla) is added to improve cohesion. The coffers are left in place for a few days, allowing the material to harden. Once ready, the coffers are lifted off and a new layer is added. The timing of activities, and the organisation of a relatively large workforce, especially if working on large-scale construction such as town walls, are critical. As a town intimately involved in the Trans-Saharan slave trade, and where the use of slave labour was part of the local economy, it quite possible, therefore, that enslaved Africans were directly involved in the construction of Zuwīla’s fortifications, and the surviving walls may be the most tangible evidence for their presence since archaeologists have yet to identify precisely where they lived or were sold, or where some of them might even be buried.

Related Primary Sources

- Medieval Slavery in Zuwīla: Archaeological and Textual Sources

- Source 2: Al-Bakrī, The Book of Highways and Kingdoms (Kitāb al-masālik wa-l-mamālik)

- Source 3: Ibn Baṭṭūṭa, Travels (Riḥlāt)

- Slave Trading at Kilwa: Archaeological Perspectives

Related Secondary Sources

- Mattingly, D.J., C.M. Daniels, M.J. Sterry and D.N. Edwards. “The walls of medieval Zuwila.” Libyan Studies 46 (2015): 35-56.

- Mattingly, D.J., M.J. Sterry, and D.N. Edwards. “The Origins and Development of Zuwīla, Libyan Sahara: An Archaeological and Historical Overview of an Ancient Oasis Town and Caravan Centre.” Azania: Archaeological Research in Africa 50, no. 1 (2015): 27-75.